COMPANY JETSTONE

Industry 4.0 in stone processing

Automated processes make volume production possible in the first place: Jetstone has already put such a fully automated line production system into operation. STEIN magazine reports.

Process automation and robotics

According to a study by management consultants Horváth and Partners, nine out of ten decision-makers are convinced that robot-controlled process automation (RPA) would greatly benefit their company. There are also companies that manufacture in series in the stone processing industry; the expansion of the sector to include engineered stones and ceramics has ensured this. These companies with automated production lines are gradually developing towards Industry 4.0. As a result, machine development in the stone industry is also undergoing a strategic and technological upheaval.

CSA 598 WJ Twin,

CSA 598,

WSR 9000,

BAZ 595 D

In stone processing in Germany, two forms of production are moving in opposite directions. One, the traditional production of gravestones, has almost come to a standstill. Although machine technology has replaced a large proportion of manual work here too, this process is almost complete. In many companies that had upgraded at the start of mechanization, equipment is now even at a standstill because it was not needed to the extent that was initially assumed. While some companies are increasingly reselling finished goods, others have specialized in custom-made products and individual items.

The production of prefabricated parts made from slab materials is developing in the other direction – here, natural stone slabs were initially joined by engineered stone slabs and then increasingly by ceramic tiles. Kitchen worktops in particular are produced in series in this way. And the end of the line has not yet been reached, as industrialized production has so far only corresponded to the age of Industry 2.0. Computerization and digitalization are still required to realize Industry 3.0 and 4.0 and thus correspond to the current state of modern industrial production.

Even if some sectors, such as ICT (information and communication technology) companies, are pioneers and others, such as stone processing, are laggards, the intelligent networking of machines and processes in industry will affect all sectors sooner or later.

Process-oriented worktop production

If you look across the border to the Netherlands, developments there are more advanced than in this country. Six major slab manufacturers account for 70 percent of the Dutch market for kitchen worktops: Lion Stone, Topline, Dekker, Kemie, Arte and Jetstone. Not all of them focus exclusively on kitchen worktops, but what they all have in common is that they manufacture from natural stone as well as quartz composite materials and ceramics.

At Jetstone, more than 100 custom-made kitchen worktops roll off the production line every day, and the trend is rising. Company owner John van den Heuvel expects the volume to increase significantly and is building ahead for this: In 2012 and2017, he had new halls built and in 2018, he commissioned the first fully automated line production in the newest hall, on which only quartz composite worktops are processed. In the company’s other halls, other worktops made of natural stone, ceramic and engineered stone are also produced on various, more or less automated production lines.

Success along the (entire) line

Since its foundation in 1993, Jetstone has developed into one of the leading worktop suppliers with around 240 employees, and the pace of growth has increased significantly in the last ten years or so. Steffen Langhans remembers that when he first visited Jetstone around 13 years ago, he only found a few stand-alone bridge saws from various manufacturers in the machine hall. Together with Jetstone, Burkhardt’s Managing Director developed the idea of the first belt production, although this would certainly not have been possible without the Dutch entrepreneur’s vision for the future, who was already focusing on growth in the kitchen industry at the time.

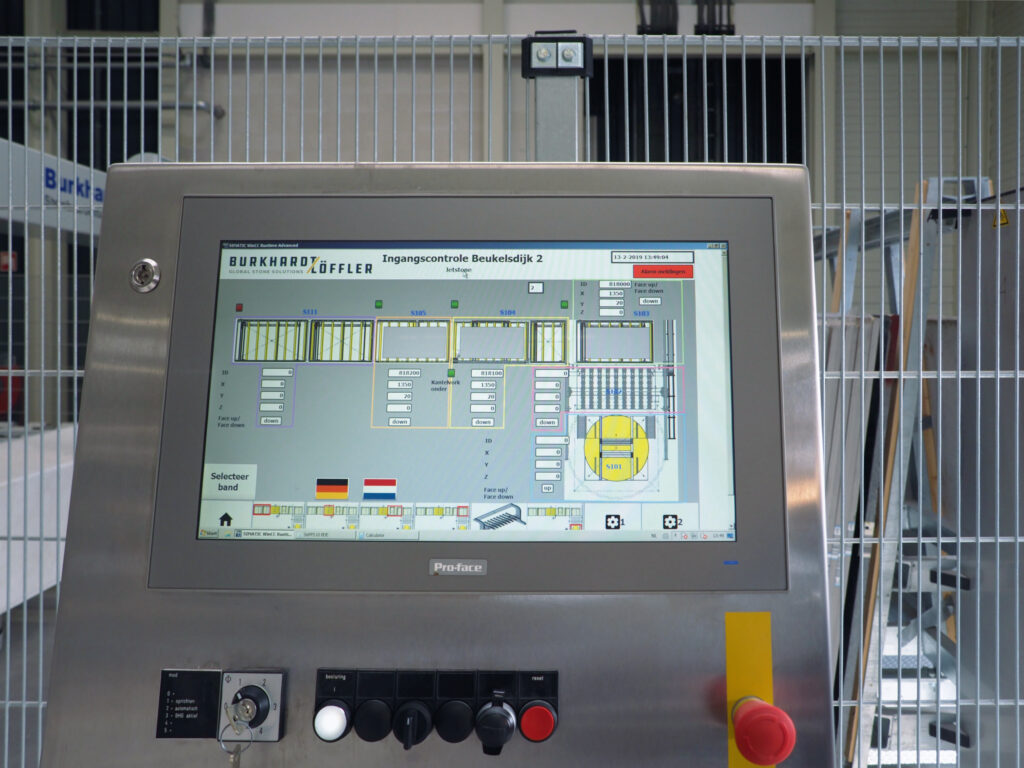

Langhans suggested initially replacing two of the three saws with a new belt production line, but keeping one of the old saws running until the new line was operating reliably – to minimize disruption to production during the conversion. At that time, the line thinking that is still practiced today was born: Jetstone put a solid line, a mitre line and a water edging line into operation one after the other. „Production was already flowing, but the machines were not yet linked,“ says van den Heuvel, looking back. His plant manager Han Verberne is pleased that he can now control the first fully automated production line developed by Burkhardt-Löffler together with the other suppliers.

Automated production line

Automated production starts at the incoming goods department with an automatic loader – a rotating A-frame onto which the panel bundles delivered by truck are unloaded, combined with a gantry manipulator (PMA 3000), which lifts the individual panels – regardless of their orientation – from the vertical to the horizontal onto a turntable (for any necessary panel alignment with the reference edge). From here, an employee calls the panels individually via automatic roller conveyors to the quality inspection station and on to the photo station, where any defects are marked. The panels, which have already been registered and cataloged in the software at this point, are then transferred to the transfer station in an area storage system, as has long been common practice in the timber industry. It is no coincidence that a system from the Dutch company Duivestein, which otherwise sets up such storage facilities in large wood processing companies and for manufacturers of engineered stone slabs, takes over here.

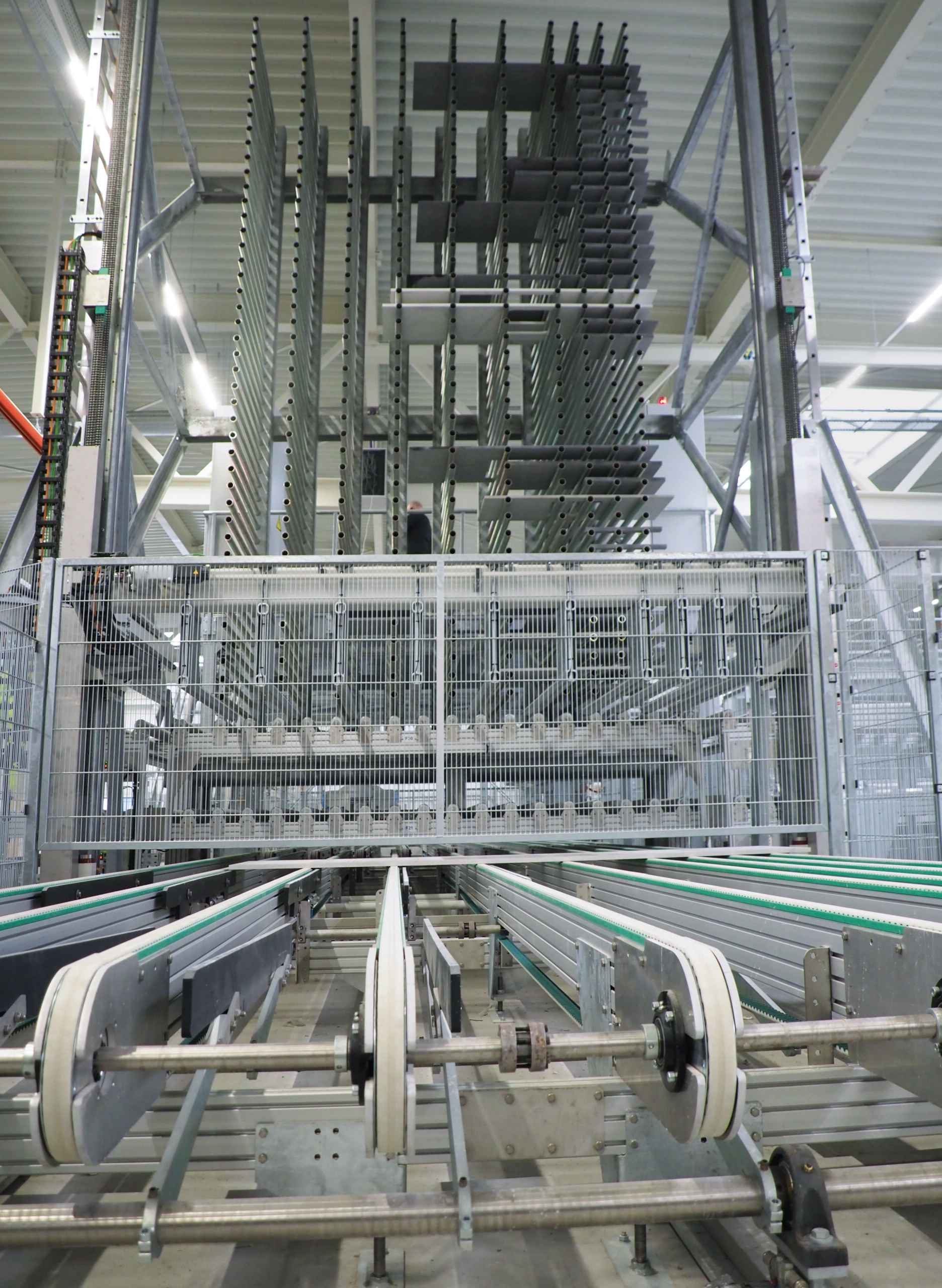

The individual panels are requested by the Burkhardt-Löffler processing machines from the area storage area as required. On a belt conveyor line with pneumatic positioning strokes, they first pass under an automatic label printer that affixes a barcode to each workpiece; this is not of interest to the machines, but only to the employee at the end of the production line who assembles the commissions. The belt conveyor then transports the panels to the CSA 598 WJ Twin rotary head bridge saw. This combines under two. This combines sawing and waterjet cutting under two bridges with an unloading manipulator. All internal cut-outs and drill holes are already carried out there at Jetstone. Cut-outs for flush-mounted sinks and hobs are also milled at the water basin using an additional milling spindle. A “normal” CSA 598 5-axis bridge saw then carries out the remaining operations, which do not require water jet technology. With its vacuum manipulators, this machine separates the workpieces to ensure an automated process. An automatic unloading manipulator sends the usable offcuts back to the area storage system. Meanwhile, workpieces are conveyed on further belt conveyor sections to a WSR 9000 sorting storage rack. The sawing unit integrated into the unloading manipulator cuts the non-recyclable offcuts into manageable small pieces, which a conveyor belt transports to a waiting disposal container.

The upper level of a two-level roller conveyor (also available with three levels at Burkhardt-Löffler) connected to the sorting storage system distributes the workpieces to two BAZ 595 D CNC machining centers with automatic rotary table and fully automatic suction cup adjustment. While the inner edges of the workpieces are being polished on the machine side (for substructure basins) or, if necessary, water grooves are milled in, the machines can already accept another workpiece using a fully automatic loading and unloading manipulator. The suction fields position themselves automatically to the size of the workpiece. Steffen Langhans emphasizes that these are the world’s first two CNC machining centers with fully automatic suction field adjustment. The processed workpieces are returned to the sorting store via the same route as to the machines, from where they are retrieved by Jetstone employees for further processing on one of two Comandulli belt edge grinding machines. The lower roller conveyor level is used here as well as another belt conveyor section, which is also equipped with pneumatic outfeeds. Finally, the finished workpieces are prepared for dispatch on an order-by-order basis. The completely digitalized process is based on systematic planning by Burkhardt-Löffler, which brought the two software companies 3Tec and SeKon on board for this purpose.

While 3Tec took care of the warehouse control system, SeKon was responsible for production management, the database connection, the postprocessors and the CAM programs, which are the same for all machines. (STEIN reported on the SePPS production planning and control system from SeKon in issue 7/2018). “Before a machine had even been installed,” explains Steffen Langhans, “all processes had already been mapped by SeKon and all Jetstone employees had been trained.”

Different market requirements in the various countries

For companies like Jetstone, Germany is an important market, but not the only one. The company has its own warehouses and assembly teams in eight north-western European countries, which are regularly supplied from the Deurneau headquarters – with products that vary greatly from country to country.

While mitred kitchen worktops made of six-millimetre-thick material already account for 70 percent of ceramic production in Germany and the Benelux countries due to demand, they are hardly available in the UK and Scandinavia. Only solid surface worktops are still sold here. On the other hand, these countries do not have such a hard time with engineered stones, says van den Heuvel. „Quartz composite was always difficult in Germany – simply because of the name artificial stone,“ says the company owner. „With ceramic as an alternative, it will be even more difficult for the material,“ he suspects. And there are also differences between the Netherlands and Germany: the ceramic sink, for example, which is doing well in Germany, cannot be sold in the Netherlands. Jetstone also produces ceramic slabs in twelve and 20 millimetre thicknesses – but only where demand requires it. Not only are the slabs more expensive than the six-millimeter material, the production time is also significantly longer; and thanks to the machine technology used, the greater thickness would not be necessary at all, explains Verberne. What has been known for many years with kitchen worktops made of wood-based materials for dry processing – the ever larger plants with „lean production“ and ever better logistics and operational organization – is now also being seen with a delay in the wet-processed boards, says Verberne. „Stone processing by skilled workers is now just a small cog in the wheel; today it’s more about processing quantities,“ says the plant manager, explaining the current steps to expand production.

Stock-based purchasing

„If you can’t produce at least 80 to 100 worktops per week, you have to specialize in order to survive,“ van den Heuvel believes. With three different materials, different panel thicknesses and, of course, the usual colors, you quickly have an enormous stock requirement. And you can’t just buy a few sheets per color and thickness, as otherwise the changing color batches would result in too much waste for the suppliers to be able to keep up with prices. That is why waste-optimized production today requires volume purchasing, says van den Heuvel. For a smaller company with inevitably order-driven production, the risk is much higher – especially as a panel can break. However, van den Heuvel and Verberne know that kitchen studios today demand standardized quality, delivery reliability and ever shorter distribution times. This is why Jetstone always has 12,000 to 13,000 raw panels in stock and is constantly anticipating what quantities of which decors need to be stocked. The 200 colors kept in stock absolutely require the stock-based purchasing practiced in the company, explains Verberne. However, the resulting delivery speed of five working days in most cases is also an important competitive advantage, in addition to the company’s flexible approach and solution-oriented way of thinking.

Interview:Know-how for optimum material flow

Burkhardt-Löffler Managing Director Steffen Langhans talks about automated production and the corresponding software in stone processing companies. In his opinion, the industry has a lot of catching up to do in this area.

STEIN: Mr. Langhans, in contrast to other companies, the Baumann Group began working on the interaction of machines for process automation at an early stage. Is this worthwhile in an industry as small as stone processing, where the majority of processing companies do not have the necessary machinery?

Steffen Langhans: It is definitely worthwhile. You can’t just look at the German market, you have to keep an eye on global developments, which have also been moving slowly in recent years. And our focus – with only one real competitor – gives us a truly unique selling point. Other countries, such as Australia, are much more open to automation. There are more assembly lines in Perthalleine than in the whole of Germany. Some of these are small stonemasonry companies, all former stand-alone machine customers who have improved their horizons and product diversity enormously thanks to process automation.

What needs to be considered when equipping machines for automated production?

My motto has long been line production. For an optimal material flow, it is advisable to network the machines with each other in a process-oriented manner, naturally with intelligent control software. This still happens too rarely in Germany, but it is what enables growth. I can provide a lot of advice here, as I have taken a close look at the large timber plants. The wood sector is at least 15 years ahead of stone processing in terms of automation – the same applies to glass production. We can and should take our cue from here, except that unlike wood, we are dealing with wet processing. The software is just as important as the automation. The machines must communicate with each other and be coordinated in such a way that they promote the production flow instead of blocking each other.

What planning steps do you and your customers of different sizes need to consider in order to ensure smooth production?

New halls would actually have to be built. In Germany, investments in machinery over the years have led to fully grafted workshop halls in growing companies. The lack of space and the incorrect arrangement of the machines then prevent efficient line production from the raw panel to the finished workpiece. A rethink is needed here: in my opinion, it would do one or two companies good to build a new, structured building on a greenfield site with sufficient space and then sell off their existing cramped production facility. This would also have the advantage that production could continue unhindered until the new production facility is operating reliably. Smaller stone processors should start automation step by step. In the first step, it is important to have a saw that can be expanded in all directions. At Burkhardt-Löffler, for example, everything can be retrofitted – from the drilling unit to the water jet system. In the second step, a CNC machining center could then be integrated – naturally also on the software side. If you keep an eye on the production flow from the outset and ensure smooth processes here, additional machines can also be added without any problems. However, without the line alignment and the space required for this, you cannot equip a company for the future. We generally develop the company-specific production solution together with our customers. Burkhardt-Löffler is known for not imposing a concept on customers, but developing customized solutions. That’s why there are no two identical systems from us anywhere in the world, only identical components.

Are you already dealing with the requirements of digitalization in production, i.e. the intelligent networking of machines and processes?

Digitalization is now standard everywhere in an automated production plant. In contrast to other industries, however, we have to deal with a lot of dirt and water in stone processing. Robots for loading and unloading, for example – as used in the timber industry – are susceptible to this. The same applies to IT control cabinets. In our industry, I recommend building bridges that offer protection against dirt and moisture. At Jetstone, we have positioned all the workstations of the new automated production line and the control cabinets on bridges above the machines and regulate loading and unloading with air; the vacuum suction cups, manipulators and suction fields provide us with sufficient stability.

What can we expect in our industry over the next few years in terms of automated production processes?

In ten years, we may have made up five to seven years of the wood industry’s lead. I wish there were more companies like Jetstone in Europe or Lechner in Germany. Then it should be possible. And I am optimistic that some companies will catch up with technological developments in stone processing.